|

Theory

of Operation:

The Quarter Shrinker uses a technique called high-velocity

electromagnetic forming.

This is sometimes called "magneforming" or magnetic pulse forming, and

is a high-energy-rate metal forming process. High-energy rate

processes apply a large amount of energy to an object for a very short

period of time. The technique was originally

developed by the aerospace industry in conjunction with NASA, and was commercialized by Aerovox,

Grumman, and Maxwell Technologies (now a subsidiary of General Atomics). EM forming uses pulsed power technology to quickly discharge high-energy discharge capacitors through a coil of wire to generate a brief, but extremely powerful, rapidly-changing magnetic field to re-shape metals inside or near the coil. Although electromagnetic forming works best with metals that have

good electrical conductivity (such

as copper, silver, or aluminum), it also works to a limited extent

with poorer-conducting metals or alloys such as nickel or steel.

In order to

shrink coins, we charge up a high voltage capacitor

bank consisting of two to four large "energy discharge" capacitors. These capacitors are specially constructed low-inductance, steel-cased capacitors that can each deliver up to 100,000 amperes (100 kA) at up to 12,000 volts. Each capacitor measures

30"

x

14" x 8", and weighs about 180 pounds. These

robustly-constructed capacitors are rated for over 300,000 discharges at

100,000 amperes per shot. A double-pole double-throw high voltage relay

is used to connect a variable high voltage AC power source through a 40 kV full-wave bridge rectifier

to charge up the capacitor bank. After the bank is charged to the

desired voltage, the HV relay disconnects the capacitor bank from the

charging supply to prevent possible damage to the rectifiers when the system is fired.

The

charged capacitor bank is then quickly discharged into

a single-layer ten-turn work coil wound from high-temperature

(polyamide-imide double-build 200C) magnet wire. The coil has an inner

diameter that is slightly larger than the initial diameter of the coin.

The coin is centered within the coil and held in place by a pair

of non-conductive polymer cylinders. The cylinders position and hold the

coin so that it is subjected to the strongest portion of

the coil's magnetic field. The cylinders also prevent the coin from

twisting or being prematurely ejected from the coil during the shrinking

process. The ends of the work coil are securely bolted to a pair of

heavy copper bus bars. A spark gap is the only affordable switch that can hold off the high voltage and then efficiently

switch the huge currents used during the coin shrinking process.

For many years, we used a custom three-terminal triggerable spark gap called a "trigatron". The

trigatron was "fired" by applying a fast rising 50,000 volt pulse to a trigger electrode, which then

caused the main gap

of the trigatron to fire. However, in order to increase the range of operating

voltages and reduce spark gap maintenance, we converted to a solenoid-driven high-current spark gap

with 2.5" diameter brass electrodes. When switched, the solenoid drives

the movable electrode towards the fixed electrode. Once the gap between

electrodes becomes small enough, the air gap breaks down,

triggering a highly-conductive arc that connects the capacitor bank to the work coil. The

electrodes don't

quite

make mechanical contact, so welding between the molten areas on the electrodes is prevented. Unlike the earlier

trigatron switch, the solenoid-driven spark-gap switch consistently

fires, never self-triggers (i.e., no high-energy

"surprises"!), and it requires considerably less

maintenance.

Once the spark gap fires, current climbs in

the

work coil at a rate that can approach five billion

amperes per second. As the work coil current increases, it creates a rapidly increasing magnetic field inside the work coil.

The resonant frequency of the resulting LC circuit (the capacitor bank

and the combined inductance of the work coil and the rest of the system) ranges between 7.8 and 10 kilohertz (kHz) depending on the diameter of the coin and the work coil. Through electromagnetic induction ("transformer action"), a

huge circulating alternating current is induced within the coin. However, due to skin effect,

the induced current in the coin is forced to flow only through the outermost rim of

the coin, forming a ring of current that's only about 1/20 of an inch thick. Because of Lenz's Law, the magnetic fields of the coin and work coil strongly oppose each

other, resulting in a tremendous repulsion force (Lorentz force) between

the work coil and the outer rim of the coin. The repulsion force is directly proportional to

the initial energy stored in

the capacitor bank. Since the capacitor bank's stored energy is proportional to the square of its voltage, doubling the capacitor voltage quadruples the peak magnetic force.

We typically use capacitor discharges with initial energies between 2,000 to 9,600 joules

(watt-seconds). Since the energy is discharged within 20-40

millionths of a second, the peak power

briefly approaches the electrical power consumed by a large city. The repulsion forces between the

work coil and the coin create radial compressive forces that

easily overcome

the yield strength

of the alloys in the coin, causing the coin's diameter to shrink. A

5,000 joule pulse reduces a US clad quarter to the diameter of a

dime. Simultaneously, powerful outward forces, sometimes called "magnetic pressure",

cause the work coil to explode

in a potentially lethal shower of copper shrapnel. Axial magnetic forces

also smash the wire turns together while the coil is simultaneously

expanded in diameter.

The magnetic forces acting on the winding are always

in a direction that tend to increase the work coil's inductance - increasing diameter and reducing the coil winding length.

During

the shrinking process, the coin behaves like a short-circuited

secondary in a 10:1 step down transformer. The peak current circulating

within

the outer rim of the coin may approach a million amperes!

A US clad quarter is typically reduced from an initial diameter of

0.955" to

approximately

0.650" within 36 millionths of a second. The magnetic forces cause the

coin's diameter to shrink at a average rate exceeding 480 miles per

hour. In US clad coins, most of

the

induced

current actually flows within the pure-copper center layer of

the clad sandwich

rather than through the poorer-conducting copper-nickel alloy cladding layers. This causes the copper center layer to

shrink a more than the outermost layers, leading to an "Oreo cookie"

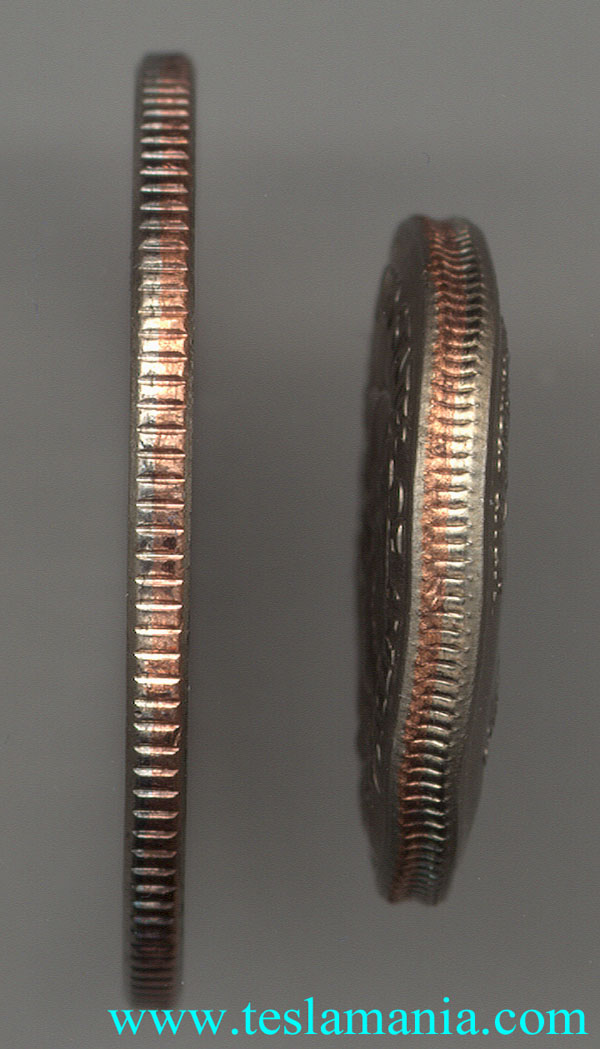

effect on the shrunken coin. The

coin

also becomes thicker as it shrinks in diameter. Despite the radical

changes to the coin, its mass,

volume, and density all remain the same after shrinking. The

Oreo

cookie and thickening effects can be easily seen in the following

edge-on image

of a normal-size and

shrunken US quarter. The slight waviness in the shrunken coin is due to

slight

force imbalances including variations in coin thickness from the coin's

surface features, and dynamic force imbalances as the work coil changes

shape before exploding. This short video clip

from the Florida State University National High Magnetic Field

Laboratory provides an excellent explanation and demonstration of

quarter shrinking. In their demonstration, they use #14 AWG magnet wire

for their work coils. We use

#10 - #14 AWG wire on our work coils depending on the size of the coin

we're going to

shrink.

In clad coins, as the copper core layer shrinks, the outer cladding

layers of the coin are pulled along for the ride, similar to the way

continental drift is thought to move continents in

the Earth's crust. This sometimes leads to "collisions" between various surface

features, and one feature may actually plow underneath another!

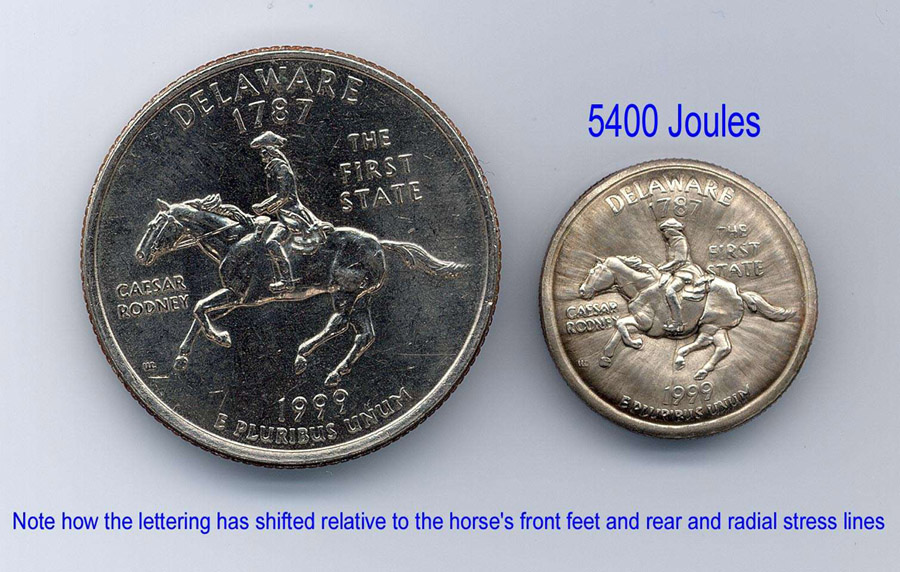

For example, note how some of the lettering on

the Delaware

quarter below have shifted so that they become partially obscured by various

parts of the horse.

Similar effects of intense magnetic forces

are sometimes seen on a much larger scale: For example, during

accidental short circuits in electrical power systems, repulsion forces

between primary and secondary windings inside large substation power

transformers or between bus bars can

literally tear the windings apart or rip bus bars from their mounting insulators.

As the

coin shrinks similar, but opposite, forces act upon the work coil's windings.

Magnetic pressure rapidly expands and stretches the copper wire in the work

coil. The film insulation peels off the wire since it can't stretch as

much as the copper! The wire coil "rapidly disassembles" (explodes!), and

fragments of the coil are blown

outward with the force of a small bomb. Small coil fragments

have been measured with velocities of up to 5,000 fps (>3400 mph, or greater than Mach

4), so the work coil must be

safely contained within a heavy blast shield. Our blast shield is made from Lexan

polycarbonate, the same material that's used

to make bulletproof windows. Regions of the blast shield that are in the direct

path of exploding coil fragments are further reinforced with steel

armor plates. Once the work coil disintegrates, any residual energy in the

system is dissipated in a ball of white-hot plasma.

The Quarter Shrinker is designed so that any residual voltage on the

capacitor bank is safely dissipated by a bank of high-power wirewound

resistors. The system is triggered from about 10 feet away from

a remote control box. I've found (the hard way!) that 8,000 Joules is

about the maximum energy I can repeatedly use without running the risk of

fracturing the Lexan walls from the shock wave. When slammed by a

high-intensity shock wave, Lexan does indeed shatter - I've got the

pieces to prove it! Other

experimenters

(Rob Stephens, Bill Emery, Phillip Rembold, Ross Overstreet, Brian

Basura, Joe DiPrima, and Ed Wingate) have resorted to using 100% steel enclosures

when running at higher power

levels.

Adding strategically-placed steel plates has stopped our Lexan blast

shield from

fracturing. We've found that AR400 steel plates (also used for armor in some miltary vehicles)

are well suited to surviving repetitive bombardment from supersonic

coil shrapnel. But even these must be periodically replaced after a couple

thousand shots.

Following

is a video made by our friends Physics Girl and Joe DiPrima which

describes in detail just how coin shrinking actually works. Included is a short

segment of some high speed video that was captured by the amateur

scientists at Hackerbot Labs (Seattle, WA). By using a special

180,000 frame/second camera they were able to capture a sequence of images of coins AS THEY WERE BEING SHRUNK (video time 1:02 - 1:24).

Because the shrinking process occurs so

rapidly, the actual "shrinkage" is only seen during a few consecutive

frames - about 40 millionths of a second in real time.

Our Results:

The largest coin we've ever shrunk was a US Silver Eagle,

a pure silver

coin that was reduced from 1.6" in diameter to 1.3" after a 6300 Joule shot. At similar energies, a Morgan

silver dollar

is reduced from about 1.5" to 1.25" in diameter, and a clad Kennedy

half dollar is reduced to the diameter of a US Quarter.

At 5,000 joules, US clad quarters shrink to the diameter of a dime.

A few years ago, physicist Dr. Tim Koeth and I took various measurements

of work coil current during the shrinking process. These showed that

the work coil consistently failed shortly after the first current peak.

Fortunately, virtually all of the coin's

shrinkage has occurred by this time. Disintegration

of the coil helps to reduce voltage reversals that could damage, and eventually destroy, the energy discharge capacitors.

The combination of high peak currents and oscillatory discharges

is extremely demanding on capacitors. Because of

premature failures with earlier GE pulse capacitors, the current system uses low inductance Maxwell (now General Atomics Energy Products - GAEP) pulse capacitors that are designed to safely cope with this abuse. While the original GE capacitors began failing

after only 50 - 100 shots, the trusty Maxwell capacitors have withstood

well over 7,000 shots with nary a whimper.

Examination of the coil fragments show that the wire has

been substantially stretched (#10 AWG looks like #14 AWG afterwards),

it becomes strongly work hardened, and it has periodically "pinched" regions and kinks

caused by the copper being stressed far beyond its yield strength by the

ultrastrong pulsed magnetic field. Many fragments are less than 1/4" long, and all

pieces show evidence of tensile fracture at the ends. Since the wire's insulation

gets blown off, most fragments are bare copper. The wire often also shows signs of localized melting

on the innermost surface of the solenoid due to "current bunching" from the combination

of skin effect and proximity effect.

The

Quarter

Shrinker works very well on clad dimes, quarters, half dollars,

Eisenhower, silver Morgan and Peace Dollars, Susan B. Anthony,

Sacagawea, small Presidential dollars, and many foreign coins.

It works less well with nickel and nickel-copper coins, and

it has virtually no effect on plated steel coins. It also works well with

older

bronze and copper-zinc alloy pennies. However, since mid-1982, US

pennies

have been made using a zinc core with a thin copper overcoat. During

shrinking,

the thin copper layer vaporizes and the zinc core melts, leaving an

unrecognizable

disk of molten zinc accompanied by a messy shower of zinc globules

throughout the

blast chamber.

Because of the greater hardness and much poorer electrical conductivity

of nickel-copper alloys, the shrinking process doesn't work as well

with US

nickels, shrinking them by only about 10% even at 6,300 Joules. Larger

copper-nickel coins, such as the UK Churchill Crown, seem to be almost

impervious to shrinking even at 6,300 Joules - this coin is as tough as its namesake!

A

shrunken coin weighs exactly the

same as it did before shrinking. As the coin's diameter shrinks, it becomes

correspondingly thicker, but its volume and density remain

the same. Bimetallic foreign coins (with rings and

centers made from different alloys) often show different degrees of

shrinkage based

upon the individual electrical conductivity and hardness of the respective alloys. In

some cases, the

center portion shrinks a bit more, loosening or sometimes even freeing

it from the outer ring. Complete separation occurs with older

Mexican, UK, and French bimetallic coins, and with newer Two Euro bimetallic coins.

Because

of

the extremely high discharge currents

and fast current rise times, capacitors rated for energy discharge applications must be designed

to

have high mechanical strength and very low inductance. They use special internal construction

techniques to

safely handle mechanical stresses created by strong magnetic and electrostatic forces

during fast, high-current discharges. When we first began coin shrinking, we used some GE

energy discharge capacitors that were simply not constructed for this type of abuse,

and unbeknownst to us, magnetic forces began tearing them apart during every shot. One

unit actually

suffered an internal electrical explosion that ruptured its metal

case, causing it to hemorrhage stinky, arc-blackened capacitor oil and aluminum foil fragments all over the floor.

The wife was not amused! Our Maxwell energy discharge

capacitors have proven to be true

"Timex's" of the pulsed power world - they continue to "take a lickin' and keep on

tickin'".

2/4/14

Update - One of our Maxwell capacitors finally failed. While charging

the bank, a muffled bang was heard, the bank voltage

abruptly plunged from about 8 kV to zero, and the mains fuse in the

power controller blew. The problem was traced to a catastrophic failure of one of the Maxwell

capacitors. The failing capacitor developed an internal short

circuit,

and all of the stored energy in the capacitor bank (~4.5 kJ) was

abruptly dumped into the internal fault. Fortunately, the heavy steel

case didn't rupture, so I was spared cleaning up several gallons

of castor oil. This capacitor, and an identical mate, had survived over

6,000 "shots" in the quarter shrinker, so I'm very satisfied with its

performance. Further research determined that the root cause of the

failure was not lifetime-related, but was due to an extended period of

abnormally low temperatures. These capacitors use a combination of kraft

paper and

castor oil for the dielectric system that separates the foil plates. The

Quarter Shrinker resides in an unheated patio.

Although cold temperatures had not been a problem during previous

winters, 2014

was abnormally cold in the Chicago area. When the capacitor's internal temperature fell below -10C

(14F), the castor oil began to partially solidify. As castor oil

solidifies, its dielectric constant drops from 4.7 to about 2.2. During solidification, small

amounts of dissolved water (that were previously harmlessly in

solution), were driven out of solution and absorbed by the kraft paper.

The reduced

dielectric constant increased the voltage

stress on the kraft paper dielectric while the absorbed water

simultaneously reduced its electrical strength. The result was sudden

dielectric failure and catastrophic short-circuiting of the capacitor.

We've subsequently installed flexible silicone electrical

heating elements to the

sides of the capacitors to always keep them toasty

(above 40F) during even the coldest days. This will prevent any future

freezing problems. With the new heaters in place, the winters of 2015 -

2018 were nicely uneventful.

Can Crushing:

A larger diameter 3-turn work coil, operating at lower power

levels, is used to crush aluminum cans. An aluminum soft drink can ends up looking

like an hourglass as the center is shrunk to about half its original diameter.

During can crushing, the coil does not disintegrate due to its more massive design

(#4 AWG solid copper wire) and because the system is fired using lower energy

levels than coin crushing. At higher power levels, the can is

ripped apart from the combination of the air inside the can suddenly being

compressed, and heat-softening of the can from the induced currents. Can crushing

also works with steel cans, but the can undergoes greater heating and reduced

shrinkage because of steel's lower electrical conductivity. The "skin depth" in steel is also

much smaller due to its ferromagnetic properties. Since

the work coil is not destroyed during can crushing, the capacitor bank and

spark gap are more heavily stressed by the oscillatory ("ringing")

discharge.

The

capacitor bank voltage must be reduced to so that the ~100% voltage reversals

don't overstress the pulse capacitors' dielectric system.

Since most of the capacitor bank's initial energy ends up being dissipated as

heat

in the spark gap, can crushing also causes significant heating and

erosion of the electrodes in the high voltage switch.

Is Wire Fragmentation Consistent with EM Field Theory?

Copper wire fragments from the work

coil clearly indicate that the wire has been subjected to large tensile stresses.

Most of the observed effects on the wire can be explained by hoop stresses

created by the combination of magnetic pressure

within the work coil solenoid, Lenz's Law repulsion

between the coil and the coin, and periodic conductor necking. The

latter occurs when magnetic

pinch forces are sufficient to cause the conductor to behave as though

it were a conductive fluid. Because of pinch instabilities, the wire becomes periodically pinched off

and broken. However, there is also a

curious ridge which shows

up under microscopic examination of the coil fragments that may hint of

other

effects as well. This artifact was first noticed by Richard Hull of the

Tesla

Coil Builders of Richmond, Virginia (TCBOR) when reviewing similar wire

fragments

from another researcher (Jim Goss). It seems that when an extremely

high

current flows through a solid or liquid metallic conductor, certain

effects

begin to appear which may not be fully explained by existing EM field

theory

and Lorentz forces.

One very interesting example involves forcing a very large

current pulse very quickly through a straight piece of wire. Under

appropriate

conditions, the wire does not melt or explode. Instead, it fractures

into

a series of roughly equal length fragments, with each fragment showing

unmistakable

evidence of tensile failure. Following is an example (from Jan Nasilowski, (1964) "Unduloids and Striated Disintegration of Wires".

Each segment was literally pulled

apart from neighboring fragments with little or no evidence of necking

or melting. Clearly large tensile forces were set up within the wire

during

the brief time that the large current flowed. But, per existing EM

theory,

no tensile forces should exist, implying that the current theory of how

Lorentz forces act on metallic conductors may be incorrect!

A father and son team of physicists,

Dr.'s Peter and Neal Graneau (coauthors of "Newtonian Electrodynamics"

and "Newton Versus Einstein")

theorize that internally developed "Ampere' tensile forces" may account

for the observed behavior of this, and other high-current experiments.

While Ampere' tensile forces are predicted by classical electromagnetic

theory, they have long been removed from all modern textbooks, being replaced

instead by modern field theory and Lorentz forces. Interestingly, even though Ampere' forces

are no longer an accepted part of current EM theory, their existence appears to be experimentally

verifiable in exploding wires or high DC current flow within molten metals (such as aluminum refining).

In their books, the Graneau's provide many thought-provoking

experiments

that appear to support Ampere' Tension forces. More recently, other

scientists have proposed that high-current wire fragmentation may actually be

caused by a combination of flexural

vibrations and thermal shock. However, we suspect that the jury is

still out on this issue, and its an area that's ripe for

additional research and experimentation.

Isn't Mutilating Money a Federal Offense?

US Federal law specifically forbids

the "fraudulent mutilation, diminution, and falsification of coins" (see

US

Code, Title 18 - Crimes and Criminal Procedure, Part I - Crimes, Chapter

17 - Coins and Currency, Paragraph 331). However, the key word is Fraudulent.

Although

it recently became illegal to melt pennies or nickels or to export them

to reclaim their value as scrap metal, you can otherwise do pretty much

anything to US coins as long as you don't alter them with an intent

to defraud. This includes squashing

them on railroad tracks, flattening them into elongated souvenirs at

tourist

traps... or crushing them with powerful electromagnetic fields. I

take great pains to

tell folks exactly what they are receiving and how the process was

accomplished.

So vending machines in tourist traps that squash

pennies

into elongated souvenirs or "funny" stamped pennies with Lincoln

smoking

a cigar are legal (although the coins can't be used as currency

anymore). In an opinion letter, folks at the US Mint "frown on the despicable practice"

of

altering coins, but they agree that it is quite legal to shrink

coins.

Note that this is not always the case within other countries! For example,

in the

UK and Australia, defacing the Queen's image on a coin may be

considered a punishable offense.

Paragraph

332

deals with debasement of coins; alteration of official scales,

or embezzlement of metals. Since most of the coins we shrink are made

from base metals, this section does not apply. However, since the density, metal

content, and weight remain unaltered during the shrinking process, coin

shrinking is legal even when applied to bullion coins made from precious metals,

and most larger gold and silver coins shrink quite nicely. HOWEVER, shrinking US paper money is indeed

illegal. Even though we are aware of a couple of chemical processes that

can shrink dollar bills to about half their original size, we do not

make or

sell "shrunken dollar bills", since defacing paper currency is indeed

illegal.

See Paragraph 333 for details.

Are you the nut who invented this device?

No, it wasn't this nut! We just perfected the technique. For the history of coin

shrinking, check out The

Known History of "Quarter Shrinking"

|

There s always a hole in theories somewhere, if you look close enough

Mark Twain, Tom Sawyer Abroad , Charles L. Webster & Co., 1894

|

Other References:

Following are various references for the serious researcher.

As many are out of print, you may also wish to check the "Out of Print Books Information" and "In Print Book Sources" sections of the Links Page, or check with your local technical college library system.

A. Electromagnetic Metal Forming and Magneto-Solid Mechanics:

1. ASM, "Metals Handbook, 8th Edition, Volume 4, Forming", American Society for Metals

- see section on Electromagnetic Forming (out of print)

2. Wilson, Frank W., ed., "High Velocity Forming of Metals", ASTME,

Prentice-Hall, 1964, 188 pages (out of print)

3. Bruno, E. J., ed., "High Velocity Forming of Metals", Revised, edition,

ASTME, 1968, 227 pages (out of print)

4. NASA, "High-Velocity Metalworking, a Survey, SP-5062", National Aeronautics

and Space Administration, 1967, 188 pages (out of print)

5. Moon, Francis C., "Magneto-Solid Mechanics", John Wiley & Sons, 1984, ISBN 0471885363, 436 pages (out of print)

6. Murr, L. E., Meyers, M. A., ed., et al, "Metallurgical Applications

of Shock-Wave & High-Strain-Rate Phenomena", Marcel Dekker, 1986,

1136 pages, ISBN 0824776127 (in print)

7. "Pulsed Magnet Crimping" by Fred Niell, straightforward explanation of magnetic forming (fairly technical, written by a physicist)

B. Capacitor Discharges, High Magnetic Fields, Pulsed Power/Switching, and Exploding Wires:

1. Frungel, F., "High Speed Pulse Technology", Vol. 3, Academic Press,

1976, 498 pages (Capacitor Discharge Engineering, out of print)

2. Schaefer, Gerhard, "Gas Discharge Closing Switches", Plenum, 1991,

569 pages (out of print)

3. Martin, T. H., et al, "J. C. Martin on Pulsed Power", Plenum, 1996,

546 pages (out of print)

4. Knoepfel, H., "Pulsed High Magnetic Fields; Physical Effects &

Generation ", Elsevier, 1970, 372 pages (out of print)

5. Fowler, C. M., Caird, Erickson, "Megagauss Technology and Pulsed

Power Applications", Plenum; 1987; 879 pages (out of print)

6. Vitkovitsky, Ihor, "High Power Switching", Van Nostrand Reinhold,

1987, 304 pages

(out of print)

7. Pai, S. T, & Zhang, Q., "Introduction to High Power Pulse Technology",

World Scientific, 1995, 307 pages (in print)

8. Sarjeant, W. J. & Dollinger, Richard E., "High Power Electronics",

Tab Professional & Reference Books, 1989, 392 pages (out of print)

9. Shneerson, G. A., "Fields & Transients in Superhigh Pulse Current

Devices", Nova Science, 1997, 561 pages (out of print)

10. Parkinson, David H., Mulhall, Brian E., "The Generation of High

Magnetic Fields", Plenum, 1967, 165 pages (out of print)

11. Chace, W. G., Moore, H. K, "Exploding Wires", Volume 1, Plenum, 1959, 373 pages (out of print)

12. Chace, W. G., Moore, H. K, "Exploding Wires", Volume 2, Plenum, 1962, 321 pages (out of print)

13. Chace, W. G., Moore, H. K, "Exploding Wires", Volume 3, Plenum, 1964, 410 pages (out of print)

14. Chace, W. G., Moore, H. K, "Exploding Wires", Volume 4, Plenum, 1967, 348 pages (out of print)

15. Mesyats, Gennady A., "Pulsed Power", Springer, 2004, 568 pages, ISBN 0306486531

16. Nasilowski, J. (1964) "Unduloids and Striated Disintegration of

Wires", in Chase, W.G. and Moore, H.K., Eds., "Exploding Wires", Volume

3, Plenum, New York, pp295-313

C. Special Reading for

those wishing to delve deeper into some more "interesting" areas of EM

Field Theory and Wire Fragmentation:

1. Graneau, Peter & Neal, "Newtonian Electrodynamics", World Scientific,

1996, 288 pages (in print)

2. Graneau, Peter & Neal, "Newton Versus Einstein, How Matter Interacts

with Matter", Carlton Press, 1993, 219 pages (in print)

3. Jefimenko, Oleg, "Causality, Electromagnetic Induction, and Gravitation",

Electret Scientific, 1992, 180 pages (in print)

4. Lukyanov, A., Molokov, S., "Why High Pulsed Currents Shatter Metal Wires?",

Pulsed Power Plasma Science, 2001, Digest of Technical Papers, Volume 2,

pages 1599-1602

5. Lukyanov, A., Molokov, S., Allen, J. E., Wall, D., "The Role of Flexural

Vibrations in the Wire Fragmentation", Pulsed Power 2000, IEE Symposium ,

pages 36/1 -36/4

6. Wall, D. P., Allen, J. E., Molokov, S., "The Fragmentation of Wires

by Pulsed Currents: Beyond the First Fracture", Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics.

36 (2003) 2757 2766

D. Web-Accessible Sources of Information about proposed "Ampere' tension" forces:

https://dflund.se/~snorkelf/Longitudinal/Slutdok.html

|